For a quarter of a century, Ohio has pursued the accountability-based “education reform” strategy that was formalized in the 2002 No Child Left Behind Act.

Ohio holds schools accountable for raising students’ scores on high-stakes standardized tests by imposing sanctions on schools and school districts unable quickly to raise scores. Ohio identifies so-called “failing” public schools, ranks them on school district report cards, and locates privatized charter schools and voucher qualification within the boundaries of low-scoring districts. Additionally, the state takes over so-called failing school districts and imposes Academic Distress Commissions as overseers. Ohio’s students are held back in third grade if their reading scores are too low, and high school seniors must pass exit exams to graduate.

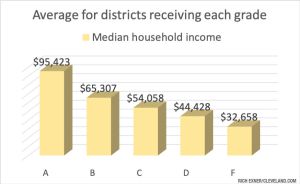

After more than two decades of this sort of school policy, student achievement hasn’t increased and test score gaps have not closed. Ohio is a state with eight big cities—Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Cincinnati, Toledo, Youngstown, Akron, and Canton; lots of smaller cities and towns; Appalachian rural areas and Indiana-like rural areas; and myriad income-stratified suburbs. Just as they do across the United States, aggregate standardized test scores correlate most closely with family and neighborhood income, not with the characteristics of the public schools. In the fall of 2019, the Plain Dealer’s data wonk, Rich Exner, created a series of bar graphs to demonstrate the almost perfect correlation of school districts’ letter grades on the state school district report card with family income.

After more than two decades of this sort of school policy, student achievement hasn’t increased and test score gaps have not closed. Ohio is a state with eight big cities—Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Cincinnati, Toledo, Youngstown, Akron, and Canton; lots of smaller cities and towns; Appalachian rural areas and Indiana-like rural areas; and myriad income-stratified suburbs. Just as they do across the United States, aggregate standardized test scores correlate most closely with family and neighborhood income, not with the characteristics of the public schools. In the fall of 2019, the Plain Dealer’s data wonk, Rich Exner, created a series of bar graphs to demonstrate the almost perfect correlation of school districts’ letter grades on the state school district report card with family income.

But while Ohio has punished so-called “failing” schools, it hasn’t done much to help the public schools in Ohio’s poorest communities. In profound testimony before the Ohio State Board of Education in early April, Policy Matters Ohio’s Wendy Patton described several decades of fiscal realities for Ohio’s 610 school districts, conditions that have accompanied the decades of punitive accountability: “(T)he state provided slightly more than half of the funding for Ohio schools, on average, in 1987, but since then local dollars have paid for the greater part of funding… Gov. Ted Strickland narrowed the gap over his 4 year term…. But Gov. John Kasich promptly reversed that effort with a $1.8 billion cut to school funding imposed over the two-year budget of 2012-13. School funding has lagged ever since. By 2020, the state share of school funding had fallen to its lowest point since 1985.”

Patton continues, noting that state funding has been not only inadequate but also unstable: “Lawmakers have allowed state funding for Ohio’s public schools to rise and fall over time, adjusted for inflation. They also changed the formula for granting state aid four times over the past dozen years. Uncertainty in state aid made planning and staffing hard for districts… Poverty affects children’s ability to learn, and concentrated poverty makes it worse. In the first years following the Supreme Court finding (DeRolph case), educators persuaded the legislature to provide extra funding for students experiencing poverty. But over time the number of economically disadvantaged students in Ohio rose, but funding did not keep pace.”

While Ohio’s legislature has doggedly enacted punitive school accountability and at the same time allowed school funding to collapse, however, in recent years a philosophical divide in the legislature has emerged and widened on the subject of public school funding. Despite that both of Ohio’s legislative chambers are now dominated by Republican supermajorities, the Ohio House, led by Bob Cupp, passed a major Fair School Funding Plan last December, a plan that meets the 24-year—until now unfulfilled—mandate of the Ohio Supreme Court’s decision in DeRolph v. Ohio. The Ohio House passed the Fair School Funding Plan by an overwhelming margin of 87-9 and sent it to the Senate, where Senate Finance Committee Chair Matt Dolan and incoming Senate President Matt Huffman killed the plan at the end of the legislative session by refusing to bring it to the floor for a vote.

In early February in the Ohio House, sponsors immediately reintroduced the Fair School Funding Plan at the beginning of the new legislative session. Then the Ohio House folded the plan into the proposed FY 2022-23 biennial budget, which the House passed on Wednesday and sent forward as HB 110 to the Ohio Senate. Although the need for a new school funding plan has been exhaustively demonstrated, there is widespread worry that the fate of the Fair School Funding plan rests with Senator Matt Huffman, whose website defines him this way: “President Huffman is devoted to quality school choices for all families, lowering taxes and reducing regulations on Ohio’s small business.”

The Toledo Blade‘s Jim Provance describes Huffman’s careful but unenthusiastic response to the school funding plan in the new budget: “Senate President Matt Huffman (R.. Lima) raised concerns about the general level of spending in the House-passed plan: ‘Financially, the government is in good shape at the state level… That doesn’t mean necessarily all the citizens are. I think it’s easier to make decisions that can be catastrophic in the long term when, at the moment, there’s a lot of money available.'”

The Cincinnati Enquirer‘s Jessie Balmert reports the same kind of lukewarm, cautious response from Huffman: “The fate of that new school funding formula, which would be phased in over six years, is murky. Senate President Matt Huffman, R-Lima, has said he doesn’t like the price tag, and the GOP-controlled Senate is working on its own way to pay for schools.”

The thing is that Matt Huffman has not been the least bit shy about expanding his own priority for school privatization. Last November he alone revised one of Ohio’s punitive educational accountability schemes—EdChoice Vouchers—by putting the burden for paying for the vouchers on the state’s poorest school districts. In late November of last year, Huffman rammed through, without any open hearings, changes in the EdChoice Voucher program, which has for several years been funded through school district deductions. (The state counts voucher students as though they are enrolled in a school district and then removes $6,000 for each high school student and $4,650 for each K-8 student right out of the school district’s local budget for the student to pay private school tuition. The district receives the state’s per-pupil basic aid for each of the students, but in many cases the voucher extracts more money than the school district receives for that student from the state.) In November, to solidify support for the program from legislators representing Ohio’s wealthy suburbs, Huffman revised the program so that only students in federally designated Title I schools can now qualify for EdChoice vouchers, thereby placing the financial burden of this program only on the school districts serving Ohio’s poorest children.

Now that the Fair School Funding Plan has been sent to the Ohio Senate as part of the House budget, the worry, of course, is that Huffman’s chamber will delete the plan—developed over several years to balance the need for adequate and equitably distributed state school funding—or redesign it to save money. The plan is calculated around the actual costs of personnel like teachers, counselors, and school nurses and other basics like technology, transportation, and facilities. In a House Finance Committee hearing on December 2, 2020, Ohio school funding expert Howard Fleeter presented testimony explaining that due to a long collapse in school funding, Ohio’s school funding formula has ceased to work: “The FY10-11 school year was the last year in which Ohio had a school funding formula… which was based on objective methodologies for determining the cost of providing an adequate education to Ohio’s 1.6 million public school students. In FY12 and FY13, Ohio employed the ‘Bridge’ formula which was not really a formula at all, instead basing funding on FY11 levels. From FY14 through FY19, Ohio did have a school funding formula; however, this formula suffered from several significant deficiencies. First the base cost was not based on any adequacy methodology, instead just utilizing per pupil amounts selected by the legislature. This approach is the very embodiment of ‘residual budgeting’ which was explicitly ruled unconstitutional in the March 1997 DeRolph ruling.” Although the term “residual budgeting” sounds technical, what Fleeter means is that from FY 14 to FY 19, without considering actual school expenses, the Legislature simply set per-pupil state funding based on now much “residual” money the Legislature had left in the budget after funding all the other expenses of state government.

What would cause Ohio’s state senators to fail to address such a serious injustice for our state’s children?

What we are watching here in Ohio is a conflict in basic values between House and Senate and even between two Republicans from Lima, Ohio: Bob Cupp, the Speaker of the House, and Matt Huffman, the Senate President. Senator Huffman understands schooling from the point of view of consumerist individualism: He supports policies that encourage families to choose their children’s education privately as though they are buying a car or a selecting a smart phone. But the money to pay tuition would come from Ohio tax revenues. Representative Cupp, who has spent a long legislative career informing himself about school finance, understands our public schools, protected by the specific language of the Ohio Constitution, as the center of the social contract. Public education is an institution that epitomizes our mutual responsibility to each other as fellow citizens in a democratic experiment.

The wide support for the Fair School Funding plan expressed by the members of the Ohio House of Representatives demonstrates the values defined by the late political philosopher, Benjamin Barber: “Privatization is a kind of reverse social contract: it dissolves the bonds that tie us together into free communities and democratic republics. It puts us back in the state of nature where we possess a natural right to get whatever we can on our own, but at the same time lose any real ability to secure that to which we have a right. Private choices rest on individual power… personal skills… and personal luck. Public choices rest on civic rights and common responsibilities, and presume equal rights for all. Public liberty is what the power of common endeavor establishes, and hence presupposes that we have constituted ourselves as public citizens by opting into the social contract. With privatization, we are seduced back into the state of nature by the lure of private liberty and particular interest; but what we experience in the end is an environment in which the strong dominate the weak… the very dilemma which the original social contract was intended to address.” (Consumed, pp. 143-144)

I’m sorry to say this, Jan, but your description of schooling at present in Ohio makes it sound like a sure way to get most children to hate schools. I hope I’m wrong about that.

Pingback: Jan Resseger: Isn’t 25 Years of Failed Educational Policy in Ohio Enough? | Diane Ravitch's blog

I will send this essay to my AAUW friends. Cuyahoga County Advisory Council on Equity needs to address this devastation. Also,I need to learn about and where the lawsuit is now.

Phyllis