Here is Stanford University sociologist Sean Reardon describing in rather technical language what his research has shown for decades about a school or school district’s standardized test scores as an accurate indicator of student demographics but not a good measure of school quality:

This blog will take a two week break. Look for a new post on Tuesday, May 14.

“I use standardized test scores from roughly 45 million students to construct measures of the temporal structure of educational opportunity in over 11,000 school districts—almost every district in the U.S. The data span the school years 2008-09 through 2014-15. For each school district, I construct two measures: the average academic performance of students in grade 3 and the within-cohort growth in test scores from grade 3 to 8. I argue that average test scores in a school district can be thought of as reflecting the average cumulative set of educational opportunities children in a community have had up to the time when they take a test. Given this, the average scores in grade 3 can be thought of as measures of the average extent of ‘early educational opportunities’ (reflecting opportunities from birth to age 9) available to children in a school district. Prior research suggests that these early opportunities are strongly related to the average socioeconomic resources available in children’s families in the district. They may also depend on other characteristics of the community, including neighborhood conditions, the availability of high-quality child care and pre-school programs, and the quality of schools in grades K-3.”

Back in 2011, Reardon documented another important trend that describes aggregate test score variation across school districts. “In 1970 only 15 percent of families were in neighborhoods that we classify as either affluent (neighborhoods where median incomes were greater than 150 percent of median income in their metropolitan areas) or poor (neighborhoods where median incomes were less than 67 percent of metropolitan median income). By 2007, 31 percent of families lived in such neighborhoods,” and fewer families lived in mixed income neighborhoods. What we have watched for fifty years across America’s metropolitan areas is school resegregation by family income. As quickly growing suburbs attract families who can afford to move farther from the central city, urban and inner ring suburban school districts enroll greater concentrations of poor children.

Unfortunately U.S News and local newspapers publish competitive high school rankings as though they are a measure or school quality. A week ago, the Cleveland Plain Dealer treated readers to another one of these misguided reports by quoting this year’s U.S News ranking of the nation’s best high schools. Reporter Zachary Lewis explains that that top high schools in greater Cleveland this year are in Solon and Rocky River. “Other Greater Cleveland high schools in the top 25 in Ohio are Chagrin Falls (no 7), Hudson (No. 9), Brecksville-Broadview Heights (No. 15), Kenston (No. 15), Aurora (No. 20), and Bay High School (No. 24).

Lewis continues: “Common traits among the highest-ranked schools are those whose students scored high on state assessments for math, reading and science. These schools also had strong results for underserved student performance, focusing on students who are Black, Hispanic, or from low-income households, performance on Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate exams, curriculum breadth and graduation rates, U.S. News said.” There is a serious problem with this statement: none of these high schools serves many students who are Black, Hispanic, or from low-income households.

The point here is not that these are bad high schools. Each one is the comprehensive high schools that serves its suburban community. The point is that they serve wealthy, homogeneously white communities whose test scores are a mark of privilege, and that schools are far more complicated institutions than can be judged by the kinds of data—test scores, graduation data, and numbers of AP classes and AP exams passed—that are indicators of privilege.

In their book, A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door, Jack Schneider and Jennifer Berkshire explain: “Schools differ from other kinds of goods because they take time to understand and experience fully… Education, the quality of which is… difficult to assess, is what’s known as a ‘credence good.’ It can take months, or even years, to figure out the quality of a school… Exacerbating the issue is the fact that schools are highly complex institutions.” (A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door, (pp. 146-148)

The 2002, No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) established the idea of judging schools by comparing their aggregate standardized test scores. Education historian Diane Ravitch describes how schools in impoverished communities were punished because NCLB’s operational strategy of comparing test scores as an indicator of school quality “overlooks the well-known fact that test scores are highly correlated with family income and are influenced more by home conditions than by teachers or schools. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of public schools were closed because of their inability to meet high test score goals. All of the closed schools were in impoverished communities. Thousands of teachers were penalized or fired because they taught the children with the biggest challenges, those who didn’t speak English, those with severe disabilities, those whose lives were in turmoil due to extreme poverty.”

The Harvard University expert on the appropriate use of standardized tests Daniel Koretz wrote a book to expose the problems with the NCLB testing regime and with judging schools by their test scores and related numerical indicators: “Used properly… tests are very useful for describing what students know. On their own, however, tests simply aren’t sufficient to explain why they know it…. Of course the actions of educators do affect scores, but so do many of the other factors both inside and outside of school, such as their parents’ education. This has been well documented at least since the publication more than fifty years ago of the ‘Coleman Report,’… which found that student background and parental education had a bigger impact than schooling on student achievement.” (The Testing Charade, pp, 148-149)

Koretz explains further: “One aspect of the great inequity of the American educational system is that disadvantaged kids tend to be clustered in the same schools. The causes are complex, but the result is simple: some schools have far lower average scores…. Therefore, if one requires that all students must hit the proficient target by a certain date, these low-scoring schools will face far more demanding targets for gains than other schools do. This was not an accidental byproduct of the notion that ‘all children can learn to a high level.’ It was a deliberate and prominent part of many of the test-based accountability reforms…. Unfortunately… it seems that no one asked for evidence that these ambitious targets for gains were realistic. The specific targets were often an automatic consequence of where the Proficient standard was placed and the length of time schools were given to bring all students to that standard, which are both arbitrary.” (The Testing Charade, pp. 129-130)

Reporters often tell readers that school ratings are based on other factors besides test scores, but it turns out that many of the other factors states consider when they do the ratings are in fact based mostly on school districts’ aggregate scores. The Ohio Department of Education’s guide to understanding the state school report cards lists five areas on which the state rates public schools and school districts: Achievement, Progress, Gap Closing, Early Literacy, and Graduation. Four of the five categories in Ohio’s system depend on a school’s or a school district’s aggregate test scores, which have for years been highly correlated with a school population’s overall family income.

Douglas Downey, a professor of sociology at The Ohio State University describes his own academic research showing that evaluating public schools based on standardized test scores is unfair to educators and misleading to the public. In a 2019 book, How Schools Really Matter: Why Our Assumption about Schools and Inequality Is Mostly Wrong, Downey explains: “It turns out that gaps in skills between advantaged and disadvantaged children are largely formed prior to kindergarten entry and then do not grow appreciably when children are in school.” (How Schools Really Matter, p. 9) “Much of the ‘action’ of inequality therefore occurs very early in life… In addition to the fact that achievement gaps are primarily formed in early childhood, there is another reason to believe that schools are not as responsible for inequality as many think. It turns out that when children are in school during the nine-month academic year, achievement gaps are rather stable. Indeed, sometimes we even observe that socioeconomic gaps grow more slowly during school periods than during summers.” (How Schools Really Matter, p. 28)

Arizona State University emeritus professor and former president of the American Educational Research Association, David Berliner is blunt in his analysis: “(T)he big problems of American education are not in America’s schools… The roots of America’s educational problems are in the numbers of Americans who live in poverty. America’s educational problems are predominantly in the numbers of kids and their families who are homeless; whose families have no access to Medicaid or other medical services. These are often families to whom low-birth-weight babies are frequently born, leading to many more children needing special education… Our educational problems have their roots in families where food insecurity or hunger is a regular occurrence, or where those with increased lead levels in their bloodstream get no treatments before arriving at a school’s doorsteps. Our problems also stem from the harsh incarceration laws that break up families instead of counseling them and trying to keep them together. And our problems relate to harsh immigration policies that keep millions of families frightened to seek out better lives for themselves and their children… Although demographics may not be destiny for an individual, it is the best predictor of a school’s outcomes—independent of that school’s teachers, administrators and curriculum.” (Emphasis in the original.)

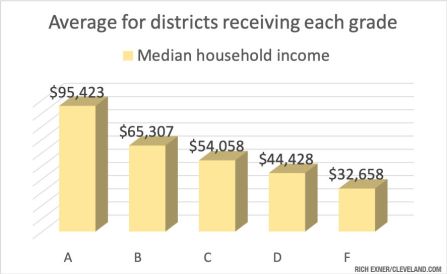

Finally, there is the simple correlation data published in 2019 by the Cleveland Plain Dealer‘s previous data wonk, Rich Exner.

Finally, there is the simple correlation data published in 2019 by the Cleveland Plain Dealer‘s previous data wonk, Rich Exner.